Structured Decoding in vLLM: a gentle introduction

TL/DR:

- Structured decoding allows precise control over LLM output formats

- vLLM now supports both outlines and XGrammar backends for structured decoding

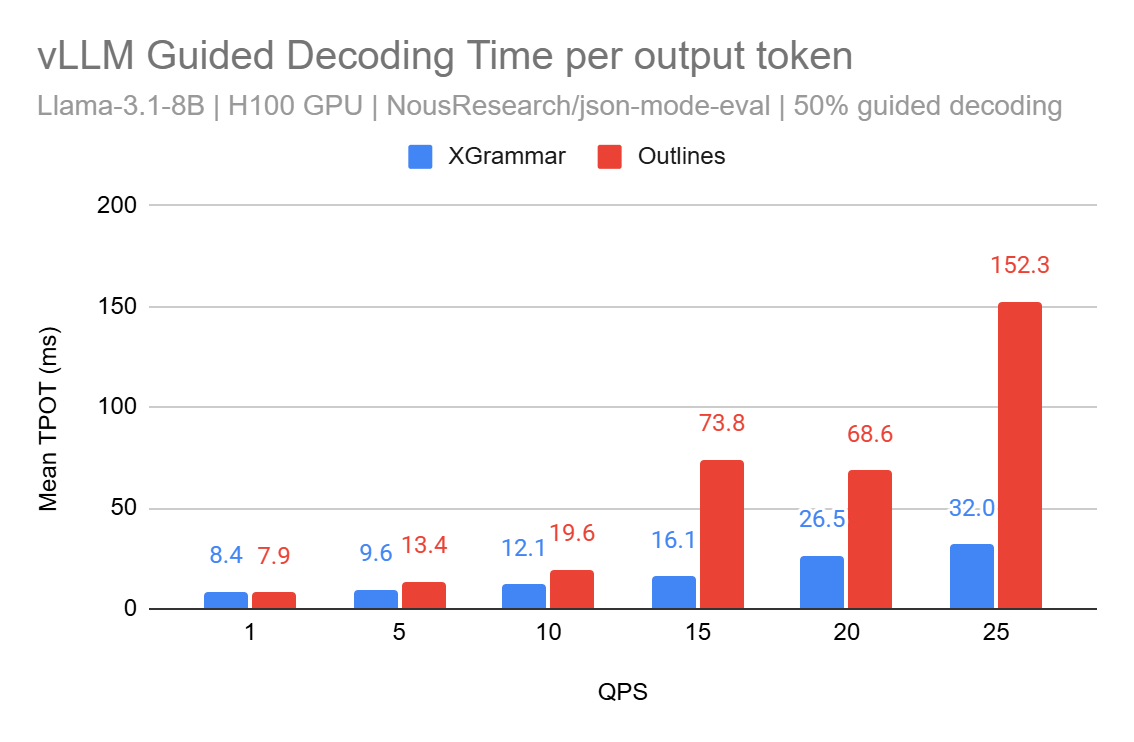

- Recent XGrammar integration brings up to 5x improvement in time per output token (TPOT) under load

- Upcoming v1 release focuses on enhanced performance and schedule-level mask broadcasting for mixed-requests batch support

vLLM is the high-throughput and efficient inference engine for running large-language models (LLMs). In this post, we will explore the annotated history of language models, describe the current state of structured decoding in vLLM, as well as the recent integration with XGrammar, and share our tentative roadmap for future improvements.

We would also invite users to tackle this blog post from a philosophical perspective, and in the process trying to posit that structured decoding represents a fundamental shift in how we think about LLM outputs. It also plays an important role in building complex agentic system.

For more information about vLLM, please check out our documentation.

Language models: A brief historical context

In 1950, Alan Turing proposed that a high-speed digital computer, programmed with rules, could exhibit emergent behaviour of intelligence (Turing, 1950). This led to two main approaches in AI development:

-

Good Old-Fashioned AI (GOFAI): A paradigm quickly emerged among researchers in the 1950s, where expert systems were designed to replicate the decision-making capabilities of a human specialist1, (or symbolic reasoning system), referred to by Haugland as Good Old-Fashioned AI (GOFAI) (Haugeland, 1997). However, it quickly ran into funding problems due to its semantic representation not being able to scale up to generalised tasks (Also known as the “AI Winter” (Hendler, 2008)).

-

New-Fangled AI (NFAI): Concurrently, Donald Norman’s Parallel Distributed Processing (Rumelhart et al., 1986) group investigated variations of Rosenblatt’s perception (Rosenblatt, 1958), where they proposed hidden layers within the network alongside with inputs and outputs to extrapolate appropriate responses based on what it had learned during training process. These connectionist networks were often built on top of statistical methods2. Given the abundance of data and Moore’s Law3 resulting in an unprecedented amount of compute available, we see the complete dominance of connectionist networks in both research and production use-cases, most notably variants of decoder-only transformers4 for text generations tasks. As such, most modern transformers variants are considered NFAI systems.

In summary:

- GOFAI are deterministic and rule-based, given its intentionality is injected through explicit programming

- NFAI are often considered as “black-box” models (in: input - out: some output), data-driven given the networked complexity nature of its internal representations

Why do we need structured decoding?

LLMs excel at the following heuristic: given a blob of text, the model will generate a contiguous piece of text that it predicts as the most probable tokens. For example, if you give it a Wikipedia article, the model should produce text consistent with the remainder of said article.

These models work well given the following assumption: the input prompt must be coherent and well-structured surrounding a given problem the users want to achieve. In other words, LLMs can be unpredictable when you need output in specific formats. Think of asking a model to generate JSON - without guidance, it might produce valid text that breaks JSON specification5.

This is where structured decoding comes in. It enables LLMs to generate outputs that follow a desired structure while preserving the non-deterministic nature of the system.

Companies like OpenAI have recognized this need, implementing features like JSON mode to constrain6 the output format. If you have built with these functionalities before (such as agentic workflows, function calling, coding assistant), chances are you are using structured decoding under the hood.

Guided decoding is to LLMs what validation is to APIs - it acts as a guarantee that what comes out matches what you expect. Guided decoding ensures structure integrity that allows developers to integrate LLMs into their application with ease!

Structured decoding and vLLM

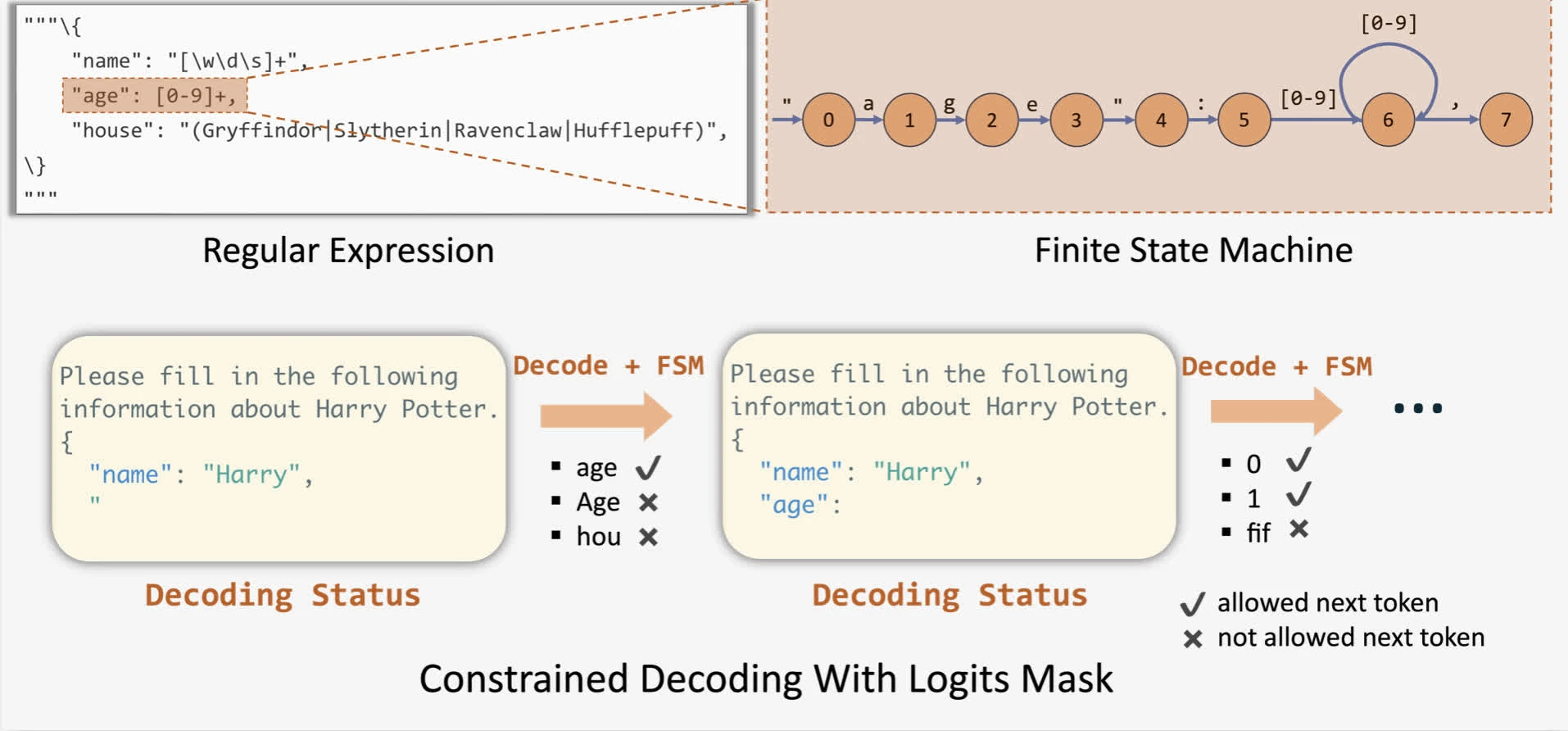

In simple terms, structured decoding gives LLMs a “template” to follow. Users provide a schema that “influences” the model’s output, ensuring compliance with the desired structure:

From a technical perspective, an inference engine can modify the probability distribution for next-tokens by applying bias (often via logit masks) for all tokens from any given schemas. To apply these biases, outlines proposed guided generations via finite-state machine (FSM) for any given schemas (Willard & Louf, 2023). This allows us to track the current state during decoding and filter out invalid tokens by applying logit bias to the output.

in vLLM, you can use this by passing a JSON schema to the sampling params (either through Python SDK or HTTP requests).

Note: in some cases, it can even improve the native decoding performance for LLM!

Previous limitations in vLLM

There are few limitations with current vLLM’s support of the Outlines backend:

- Slow decoding: FSM has to be constructed at a token-level, meaning it can only transition the state one token per step. Therefore, it can only decode one token at a time, resulting in slow decoding.

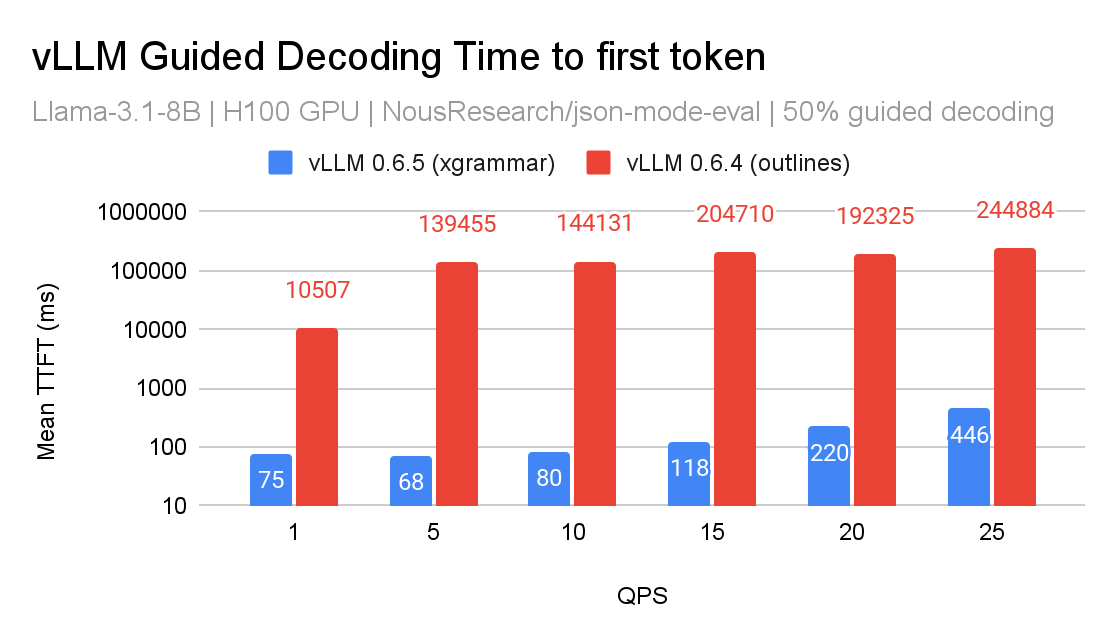

- Batch processing bottlenecks: Implementation in vLLM relies heavily on logit processor7. As such, this is on the critical path of the sampling process. In batching use-case, compiling FSM per requests as well as computing the mask synchronous means that all requests in any given batches will get blocked, resulting in high time-to-first-tokens (TTFT) and lower throughput.

- We found that compiling FSM is proven to be a relatively expensive task, making it a significant contributor to the increased TTFT.

- Performance issues with CFG mode: With outlines integrations, while JSON mode is relatively fast, the CFG mode runs significantly slower, and can occasionally crashes the engine.

- Limited advanced feature support: Techniques like jump-forward decoding are currently not possible with logit-processor approach. It requires prefilling a set of k-next tokens, whereas for logit processors we can only deal with the next-token.

Integration with XGrammar

XGrammar introduces a new technique that batch constrained decoding via pushdown automaton (PDA). You can think of a PDA as a “collection of FSMs, and each FSM represents a context-free grammar (CFG).” One significant advantage of PDA is its recursive nature, allowing us to execute multiple state transitions. They also include additional optimisation (for those who are interested) to reduce grammar compilation overhead.

This advancement addresses limitation (1) by moving grammar compilation out of Python into C, utilising pthread. Additionally, XGrammar lays the groundwork for addressing limitation (4) in future releases. Below are performance comparisons between the XGrammar and Outlines backends:

In vLLM’s v0 architecture, we’ve implemented XGrammar as a logit processor, optimizing it with caching for tokenizer data. While the performance improvements are encouraging, we believe there’s still significant room for optimization.

There are still a few usability concerns in XGrammar v0 integration to match feature parity with all use cases:

- It is yet to support grammars other than GBNF format (PR on vLLM: github)

- It is yet to support regex

- It is yet to support complex JSON that uses regex patterns or numeric ranges

- There are a few PR trying to cover this usage. There was one bugfix PR on vLLM and one upstream

vLLM now has a basic support for XGrammar by default. In case where we know XGrammar is insufficient to serve the request, we fall back to Outlines.

Note that vLLM also includes support for lm-format-enforcer. However, from our testing we found that in some long context test cases, lm-format-enforcer fails to enforce correct outputs, and not up to par with Outlines in terms of performance.

Tentative plans for v1

With the release of v1 on the horizon, we’re working on a tentative plan for structured decoding:

- Moving guided decoding towards scheduler-level:

- Reason: We have more context regarding which requests that use structured decoding at a scheduler-level, therefore it shouldn’t block other requests within the batch (tentatively addressing limitation (2)). In a sense, this moves guided decoding outside of the critical path.

- This would allow for more natural vertical integration with jump-forward decoding (address limitation (4)).

- Allowing bit-mask calculation in one process instead of each GPU workers

- Reason: We can broadcast this bit-mask to each GPU worker instead of repeating this process per GPU worker.

- We will look to carefully analyze the bandwidth implications of broadcasting masks for every sample per request that use guided decoding.

- Good baseline for speculative decoding and tool-use

- Reason: XGrammar includes plans to support tool-use, such that we can move away from Python’s tool parser.

- Tree scoring in speculative decoding can then use the same API as jump-forward decoding (which depends on the integration of guided decoding at the scheduler level).

NOTE: if you have any more suggestions we are more than happy to take it into consideration. Consider joining vLLM slack via #feat-structured-output.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the vLLM team, XGrammar team, Aaron Pham (BentoML), Michael Goin (Red Hat), Chendi Xue (Intel), and Russell Bryant (Red Hat) for their valuable feedback and collaboration on bringing XGrammar to vLLM and the continuous effort to improve structured decoding in vLLM.

References

- Bahdanau, D., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2016). Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473

- Haugeland, J. (1997). Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, and Artificial Intelligence. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/4626.001.0001

- Hendler, J. (2008). Avoiding Another AI Winter. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 23(2), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2008.20

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation.

- Kaplan, J., McCandlish, S., Henighan, T., Brown, T. B., Chess, B., Child, R., Gray, S., Radford, A., Wu, J., & Amodei, D. (2020). Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361

- Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., & Dean, J. (2013). Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781

- Rosenblatt, F. (1958). The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychological Review, 65(6), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042519

- Rumelhart, D. E., McClelland, J. L., & Group, P. R. (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing, Volume 1: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition: Foundations. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5236.001.0001

- Shortliffe, E. H. (1974). MYCIN: A Rule-Based Computer Program for Advising Physicians Regarding Antimicrobial Therapy Selection (Technical Report STAN-CS-74-465). Stanford University.

- Statistical Machine Translation. (n.d.). IBM Models. Statistical Machine Translation Survey. http://www2.statmt.org/survey/Topic/IBMModels

- Turing, A. M. (1950). i.—Computing Machinery And Intelligence. Mind, LIX(236), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2023). Attention Is All You Need. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03762

- Willard, B. T., & Louf, R. (2023). Efficient Guided Generation for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09702

-

Allen Newell and Herbert Simon’s work at RAND initially showed that computers can simulate important aspects of intelligence.

Another notable application was found in the medical domain (Haugeland, 1997). MYCIN, developed at Stanford University in the 1970s, diagnosed and recommended treatments for blood infections (Shortliffe, 1974). MYCIN’s developers recognized the importance of justifying recommendations, implementing what were known as “rule traces” to explain the system’s reasoning in human-understandable terms. ↩

-

In the 1990s, IBM released a sequence of complex statistical models that is trained to perform machine translations tasks (Statistical Machine Translation, n.d.) (see also: this lecture from Cornell).

In 2001, Bag of words (BoW)-variants model was trained on 0.3B tokens and was considered SOTA at the time (Mikolov et al., 2013). These earlier works proved to the research community that statistical modelling triumphs over symbolic counterpart for language processing given it can capture the general patterns for large corpuses of text. ↩

-

In 2017, The landmark paper “Attention is all You Need” introduced Transformers architecture (Vaswani et al., 2023) for neural machine translations tasks, which is based on the attention mechanism first proposed by (Bahdanau et al., 2016).

OpenAI then introduced the scaling law for neural language models (Kaplan et al., 2020), which sets off the race towards building these systems based on foundational language models. ↩

-

Prior to Attention-based transformers, seq-to-seq models uses RNNs given its ability for longer context length and better memory. However, they are more susceptible to vanishing/exploding gradients comparing to feed-forward network, and thus LSTM (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997) was proposed to solve this problem. Yet, one of the main problems with LSTM is that they tend to have poor memory recall with data they have seen many steps ago.

The Attention paper addresses this problem by encoding additional positional data into the inputs. The paper also additionally proposed a encoder-decoder architecture for translation tasks, however, most of text-generation models nowadays are decoder-only, given its superior performance over zero-shot tasks.

One of the many reasons why attention-based transformers works better than LSTM is because transformers are very scalable and hardware-aware (you can’t just arbitrary add more LSTM block and hope for better long-term retention). For more information, please refer back to the original paper. ↩

-

One might argue that we can reliably achieve these through few-shot promptings, i.e “Give me a JSON that yields the address of users. Example output can be …”. However, there is no guarantee that the generated outputs is a valid JSON. This is because these models are probabilistic systems, as they are “sampling” the next results based on the distribution of data that it was trained on.

One might also argue that one should use specific fine-tuned models for JSON outputs to perform such cases. However, fine-tuning often requires extensive training and a lot more labor to curate data, monitor progress, and perform evaluation, which is a huge resources not everyone can afford to do. ↩

-

Note that the phrase “[structured/constrained/guided] decoding” are used interchangeably, but they all refer to the same mechanism of “using a format for the model to structurally sampling outputs.” ↩

-

See this blog post from HuggingFace for using logit processors to control the generation process. ↩