Inside vLLM’s New KV Offloading Connector: Smarter Memory Transfer for Maximizing Inference Throughput

In this post, we will describe the new KV cache offloading feature that was introduced in vLLM 0.11.0. We will focus on offloading to CPU memory (DRAM) and its benefits to improving overall inference throughput. In the second part of the blog, we deep dive into our efforts in optimizing host-to-device and device-to-host throughput for KV offloading.

Motivation

Serving LLM models is a computationally complex operation, which at its core involves computing blobs of data known as KV data. The initial step for generating a response to a user’s prompt is the computation of the KV values which correspond to that prompt. This phase is known as the prefill stage in the request-handling lifecycle. The prefill stage, where KV values are calculated per prompt, is computationally expensive, and requires specialized accelerated hardware (such as a GPU) to complete quickly.

The KV values calculated for one prompt can be reused for other prompts that share the same prefix, to eliminate the need for recalculation. For many use-cases, caching and re-using KV values can thus achieve two main benefits:

- Improving request latency (assuming reading from the cache is faster than re-calculating the KV data)

- Increasing per-node throughput (as the load on the GPU cores is reduced, thus allowing to process more concurrent requests).

Furthermore, KV cache offloading can be useful even for workloads where requests share no common prefix. Specifically, when handling many concurrent requests, the GPU can run out of space to store the KV values required for serving the set of requests being processed. In this case, the inference engine may preempt a running request, discarding its KV values from the GPU memory. Later on, the request will be re-scheduled for processing, and so its KV values would need to be re-computed. The cost for re-computing the KV values can be avoided by offloading the KV cache to a larger tier (such as CPU DRAM) before the request is pre-empted.

CPU Offloading

In this post we put an emphasis on KV offloading to CPU memory (DRAM). This practice is of special interest for a combination of reasons:

- CPU RAM is widely available across deployments.

- Its capacity typically exceeds that of GPU memory, allowing a larger KV cache.

- Transfers between CPU RAM and GPU memory benefit from low latency and high throughput.

Combining this with the previous point, this makes CPU offloading ideal for efficiently handling preemptions of requests. - CPU RAM is also a convenient staging area for further offloading to external storage.

This is especially beneficial in cases where storage latency is high.

The New Offloading Connector

The vLLM Connector API

vLLM has long supported an API for reading and writing the KV data, integrated with the request lifecycle. This API is known as the Connector API. At a high-level, vLLM queries this API before handling any request, allowing KV data to be imported from an external source. Following KV data computation, vLLM also calls this API to store the newly generated KV values on an external target.

Originally, the connector API was synchronous. Meaning that while vLLM was externally loading / storing KV values, the vLLM engine was blocked, and no new batches of requests could be handled in parallel. vLLM 0.9.0 extended the connector API to support asynchronous loading and storing of KV data. The offloading connector utilizes this new asynchronous API for KV cache offloading.

We introduce the offloading connector, which allows for asynchronous offloading and loading of KV data. It exposes a pluggable backend API, allowing for any medium to be used for offloading. This API simplifies adding new offloading backends. You basically need to define a transfer function implementing KV data copying between mediums.

The offloading connector is bundled with a CPU backend, enabling native CPU offloading of KV data in vLLM. In the rest of this post, we will focus exclusively on CPU offloading.

Using the Offloading Connector

To use the offloading connector for CPU offloading, simply add the following CLI flag to the vllm serve command:

--kv_offloading_backend native --kv_offloading_size <size_in_GB>

This CLI assumes this PR #24498, which should hopefully be included in 0.14.0.

For older releases, CPU offloading can be enabled using the following CLI:

--kv-transfer-config '{"kv_connector":"OffloadingConnector","kv_role":"kv_both","kv_connector_extra_config":{"num_cpu_blocks": <num_cpu_blocks>}}'

where num_cpu_blocks is the number of CPU blocks to allocate for the CPU KV cache.

Benefits of CPU Offloading via the Offloading Connector

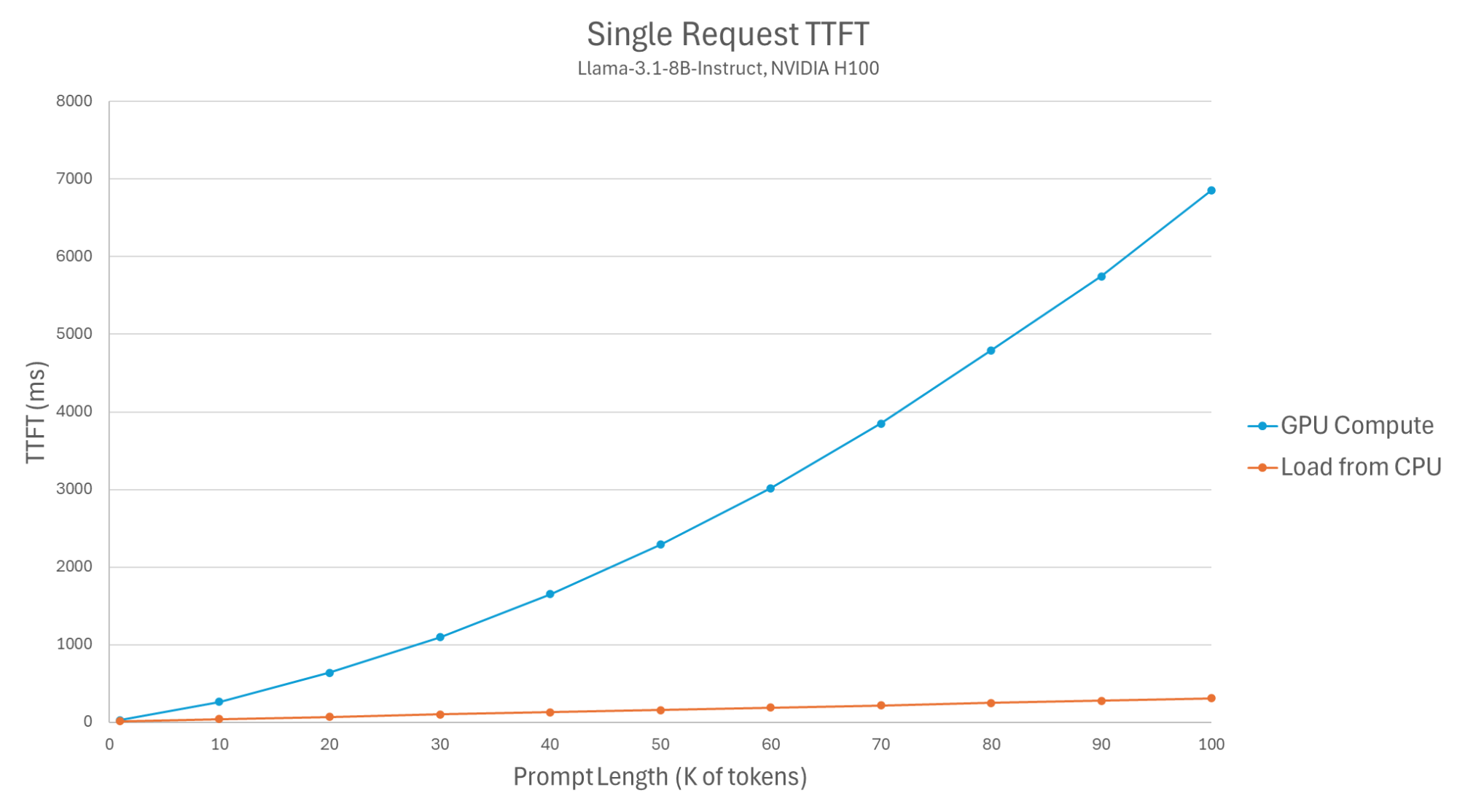

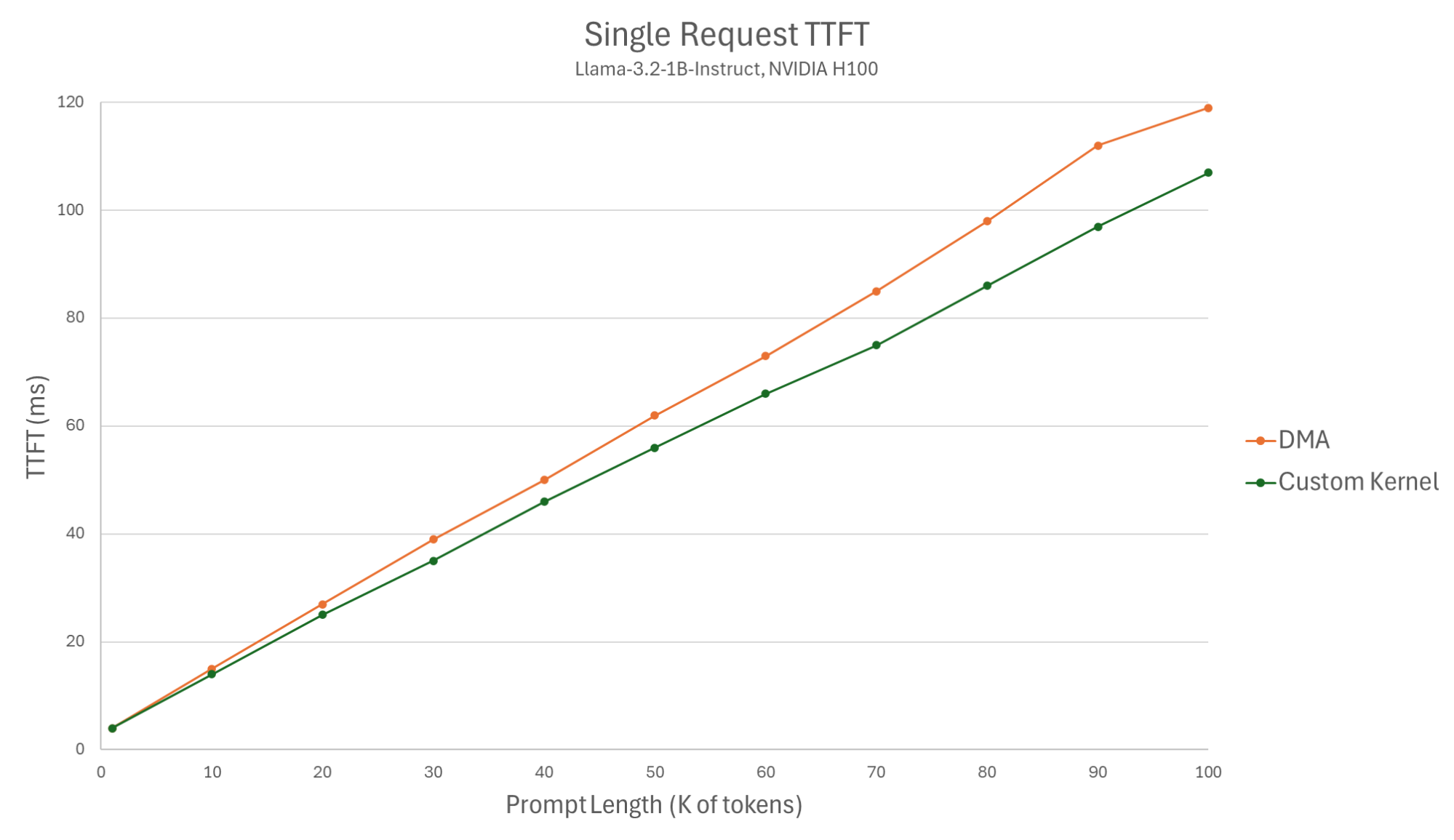

We present two distinct micro-benchmarks. The first measures the time-to-first-token (TTFT) of a single request, emphasizing the speed up of serving a single request, while the second measures the throughput of a system serving multiple concurrent requests, showing how offloading helps handle more taxing workloads.

In our first benchmark, we measure the latency of processing a single prefill request, comparing CPU cache loading to a computation of the KV values by the GPU.

Figure 1: Single request TTFT (Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, NVIDIA H100).

The results demonstrate that loading KV values from the CPU reduces TTFT by X2-X22, depending on the prompt size. The exact setup and code for our benchmarks appear at the end of this blog.

Note that the latency of KV offloading (copying KV data from GPU to CPU) is not user-facing, in the sense that it should not affect response times. This is since the offloading is also done asynchronously, and the user’s request can be completed without having to wait for this transfer to complete. This means that using the offloading connector has minimal effect on TTFT for cache misses.

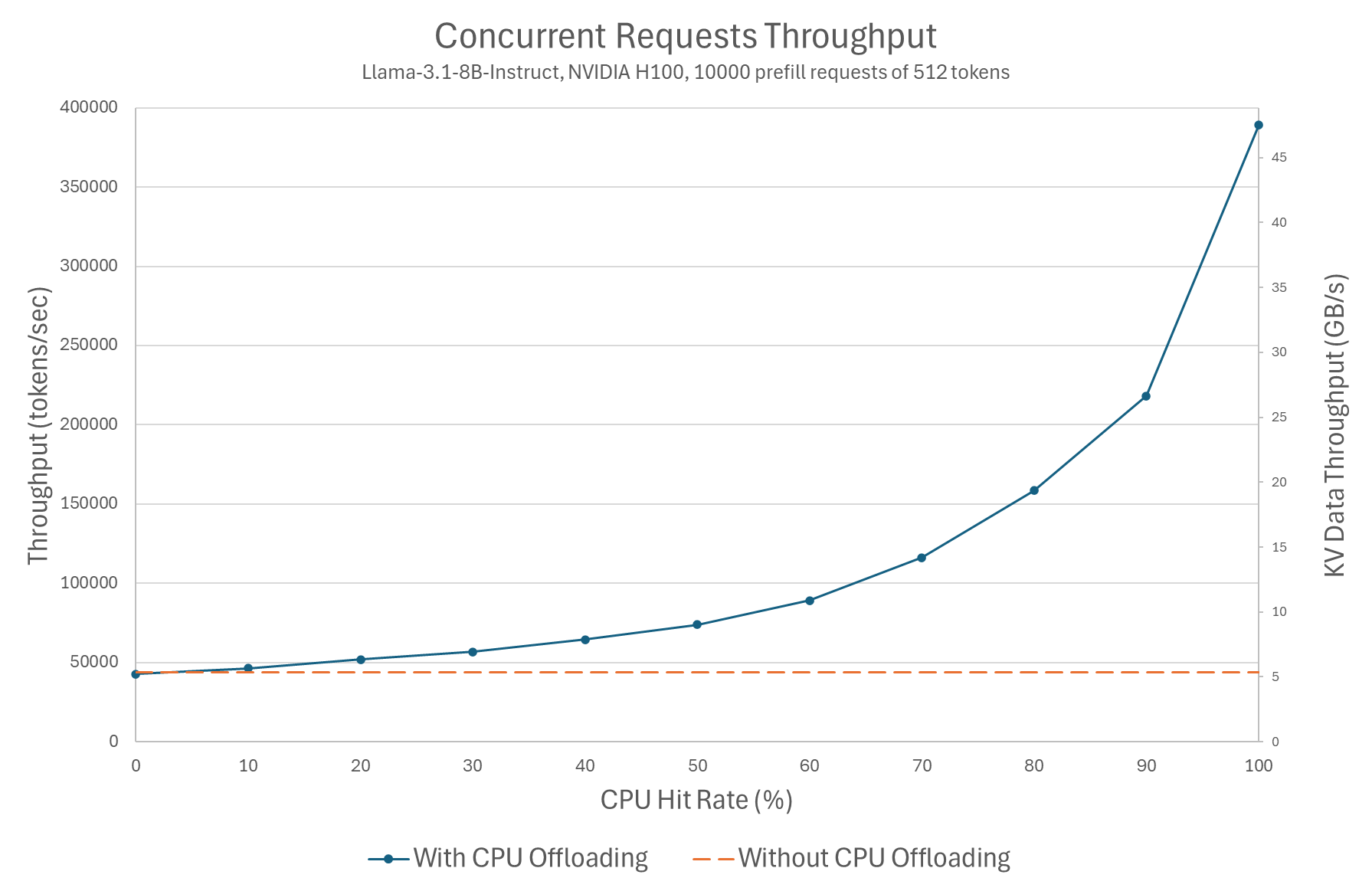

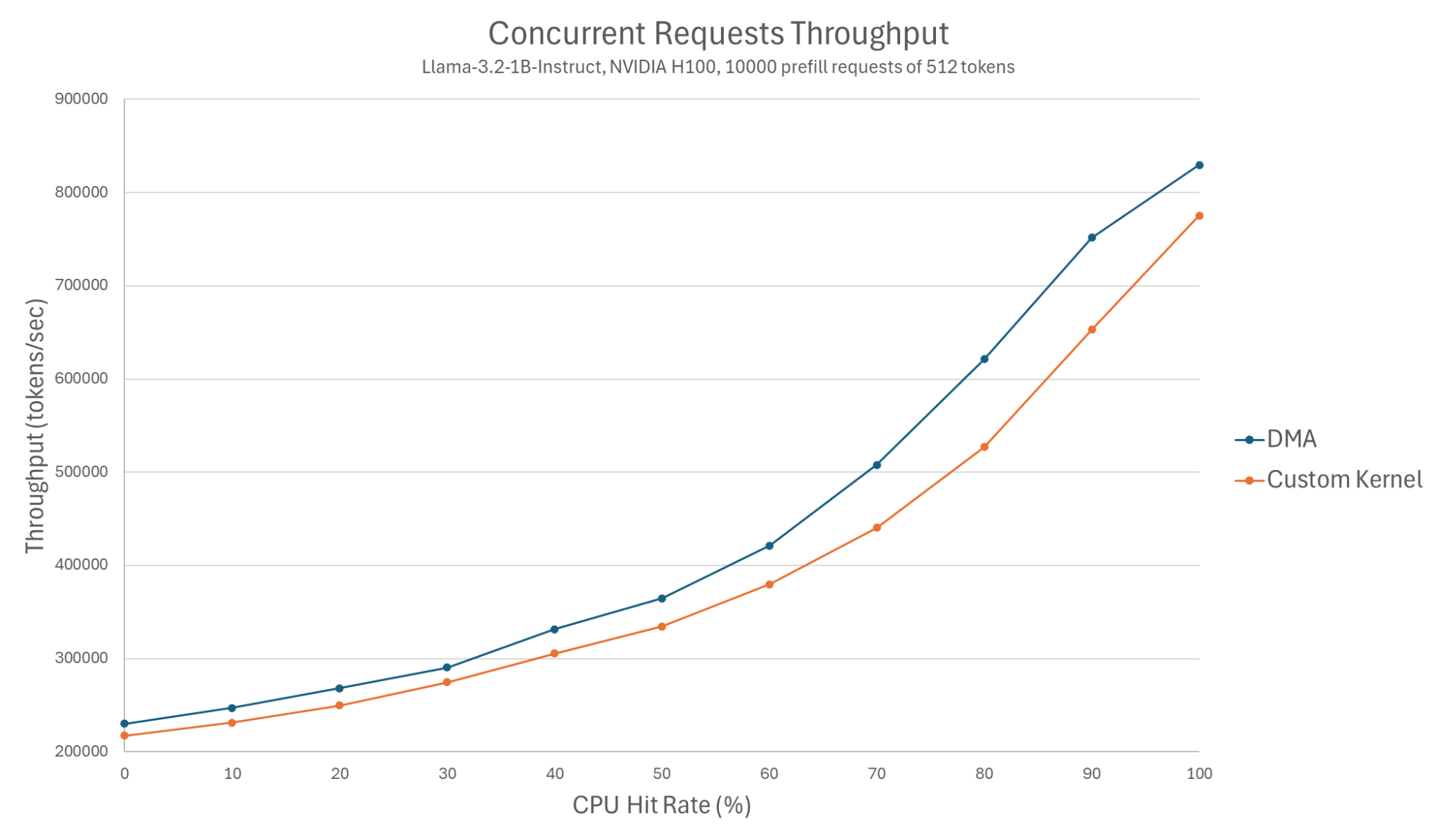

Next, we benchmark the effect of using CPU offloading on the overall throughput when handling multiple concurrent requests. This essentially submits a batch of 10,000 unique requests (each of 512 tokens), and measures the throughput achieved for various levels of hits in the CPU cache.

We measure the time to handle these requests (omitting the time to warm-up the CPU cache), and use it to deduce the throughput in token/s. The GPU cache is not utilized in order to focus on the effect of caching in the CPU.

Figure 2: Concurrent requests throughput (Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, NVIDIA H100, 10000 prefill requests of 512 tokens).

The results show throughput increases with the CPU KV cache hit rate. We observe that the throughput increases by up to X9, even though TTFT for this prompt size only decreased by X2. This demonstrates that the major gain in KV cache offloading is throughput maximization.

vLLM versions of the Offloading Connector

Note that the offloading connector performance was dramatically improved in 0.12.0. For example, testing with Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and an NVIDIA H100 GPU, we saw up to X4 reduction in TTFT, and X5 increase in throughput. We will expand on the details of this improvement in the section that discusses vLLM’s physical block size.

Further improvements will be hopefully introduced in the upcoming 0.14.0 release.

In particular:

- Enabling preempted requests to be loaded back from the CPU (PR #29870)

- Fix a race condition between offloading and model computation (PR #31341)

Our evaluation in this post includes these improvements.

Evaluating GPU-CPU Transfer Techniques

In the rest of the post, we will do a technical deep dive into some of our considerations when designing the CPU offloading. Specifically we present our research aimed to optimize inference throughput by maximizing GPU-CPU throughput while minimizing overhead on GPU and CPU cores.

As mentioned above, when defining a backend for the offloading connector the main component is a transfer function. In the case of the CPU backend, this transfer function copies data from the GPU memory to the CPU memory (and vice-versa). It currently supports CUDA-compatible devices (NVIDIA and AMD).

The transfer function implemented by the CPU backend uses the cudaMemcpyAsync function, which utilizes a hardware component on the GPU called DMA (Direct Memory Access). This component is designed for high-throughput transfers of data between the device (GPU) and the host memory. Furthermore, utilizing DMA for executing the transfer means minimal overhead on the CPU and GPU cores. This property is especially important since our transfers are running asynchronously with respect to the model computation.

DMA offers the best throughput when handling large physically-contiguous copies. This means that the performance we expect to measure for offloading will vary depending on the KV data layout. LLM models with bigger blocks of KV data will perform better.

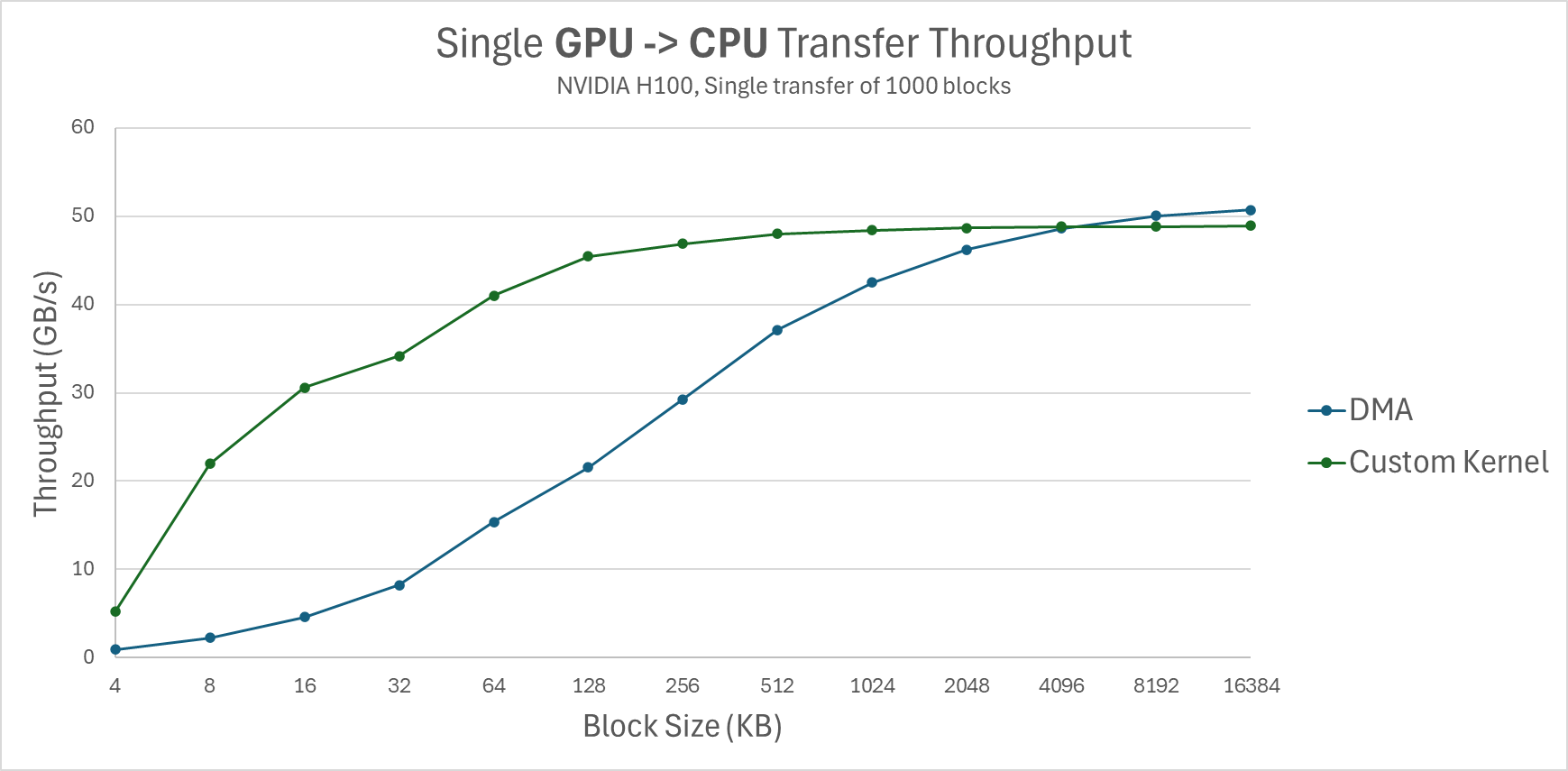

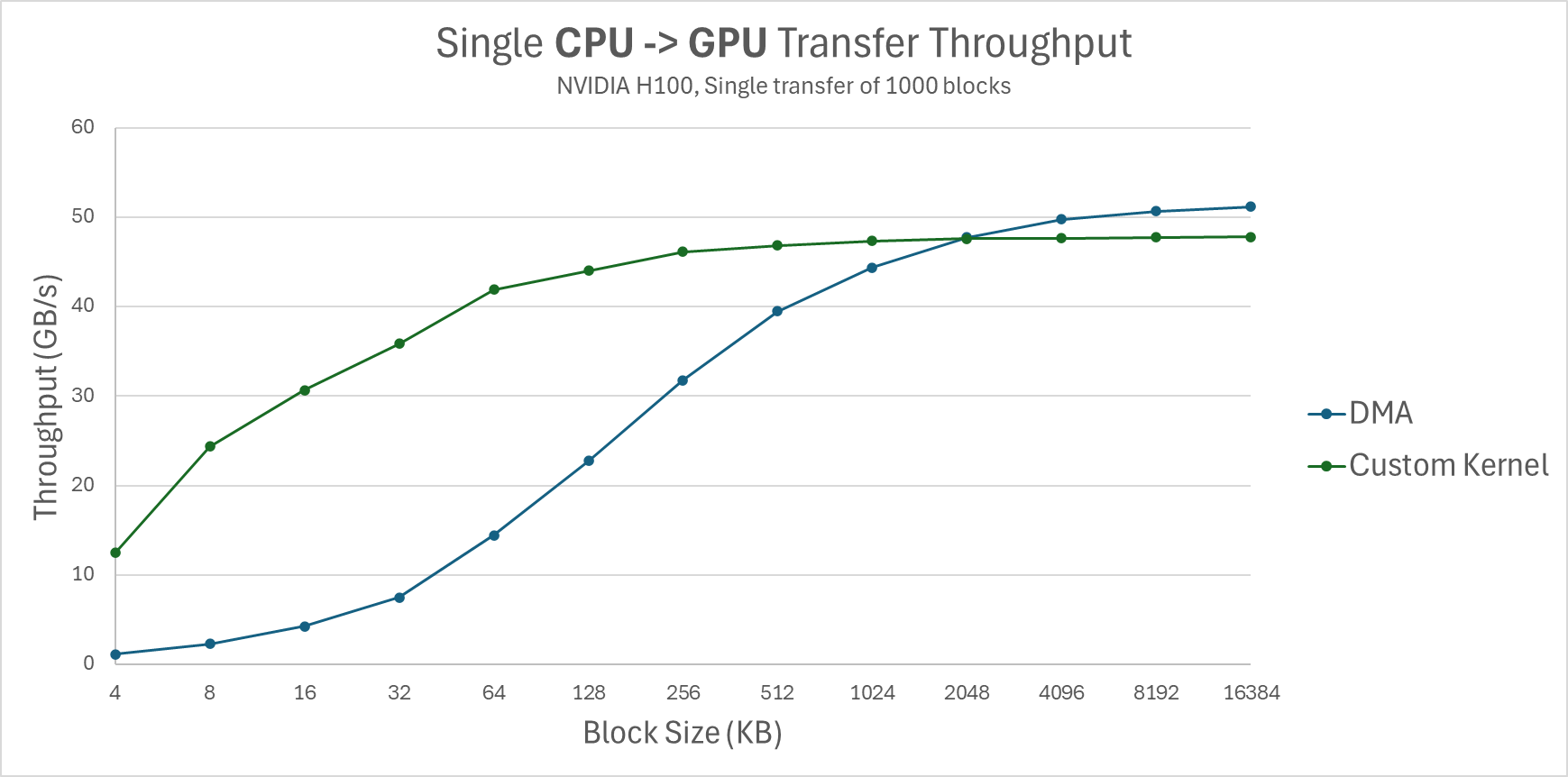

But how fast is the DMA? And how does it compare to alternatives like using a custom-made CUDA kernel?

To answer these questions we created the micro-benchmark gpu_cpu_benchmark.

In this benchmark we test two alternatives for copying data between the GPU and the CPU:

- Copying using DMA - via cudaMemcpyAsync.

- Copying using a custom CUDA kernel which utilizes GPU cores to copy 16-byte words using raw pointers. This approach is effective as it uses the massive parallelism offered by the GPU cores. On the other hand, it creates greater interference with the main tasks of the GPU cores.

Our first test measures the throughput for a single transfer of 1000 blocks, testing with block sizes ranging from 4KB to 16MB:

Figure 3: Single GPU -> CPU transfer throughput (NVIDIA H100, Single transfer of 1000 blocks).

Figure 4: Single CPU -> GPU transfer throughput (NVIDIA H100, Single transfer of 1000 blocks).

The results confirm that DMA performs well, but only for larger block sizes. For smaller block sizes, the custom kernel achieves significantly better throughput. We note however that the results of the custom kernel are more noisy, suffering a bigger variance.

We now move on to test bi-directional transfer throughput, by issuing two concurrent transfers, one for read and one for write. In this test, we fix the block size at 2MB, playing with the ratio between the size of transfers of both directions. For both copy mechanisms, the peak throughput is achieved when transferring roughly the same amount in both directions. However, although for single-direction both can get up to about 50GB/s, for bi-directional the results differ:

- DMA achieves 83.4 GB/s

- Custom kernel achieves 68.5 GB/s

So to decide between the two approaches, the question now remains:

- What is the effective block size used by vLLM?

This depends on the model being served, and the vLLM configuration. In the next section, we will answer this question for some of today’s commonly used models. - How does both approaches affect the GPU model computation performance?

Recall that the offloading connector is designed to offload / load KV data in parallel to the model computation work performed by the GPU. In our evaluation we will see how each approach affects the overall throughput.

Changing vLLM’s Memory Layout

In this section we will describe our changes to the GPU memory layout in vLLM to a format that better supports KV transfers (while not compromising computation speeds).

We start by describing the default memory layout used by vLLM for its KV cache and understand what is the size of fragments that needs to be copied between the GPU and CPU when offloading KV data. This dictates what is the effective physical block size for transferring KV data in vLLM.

vLLM allocates GPU memory in blocks of tokens, by default 16 tokens per block. The actual physical layout depends on the attention backend (e.g. FlashAttention, FlashInfer, etc.) being used and the model being served. The most common models today are uniform models, composed of multiple layers, each with its own KV cache but of the same shape. vLLM also supports hybrid models, which are currently not optimized for the offloading connector. For uniform models, vLLM allocates each layer its own KV cache, and so the KV cache of a single logical block is fragmented to num_layers blocks, one per each layer. Furthermore, depending on the attention backend, the per-layer block can be further fragmented into 2 sub-blocks, one per K (the key cache) and one per V (the value cache).

This fragmentation is meaningless for model computation performance, but is devastating for KV offloading as it creates an unnecessary fragmentation in the KV cache layout, yielding a smaller effective block size. To overcome this, we recently upstreamed a change in vLLM’s KV cache layout which creates one contiguous physical block including the KV data of all layers. This change effectively increased the physical block size by a factor of 2*num_layers, and this in turn increased the throughput of the offloading connector by an order of magnitude.

The following table summarizes some of today’s commonly used models, comparing the old (0.11.0) and new (0.12.0) physical block size (assuming vLLM is using 16 tokens blocks).

| Model | Old block size | New block size |

|---|---|---|

| deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B (tensor_parallel_size=2) | 16 KB | 2 MB |

| deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-V2-Lite-Chat (GPU block size=64) | 72 KB | 1.9 MB |

| meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 32 KB | 2 MB |

| meta-llama/Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct | 16 KB | 0.5 MB |

| meta-llama/Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct | 8 KB | 1.25 MB |

| mistralai/Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 | 32 KB | 2 MB |

| mistralai/Mistral-Small-24B-Instruct-2501 | 32 KB | 2.5 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct | 8 KB | 0.56 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen3-0.6B | 32 KB | 1.75 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct | 16 KB | 0.87 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen3-4B-Instruct-2507 | 32 KB | 2.25 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct | 8 KB | 0.44 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen3-8B | 28 KB | 1.97 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen3-1.7B | 32 KB | 1.75 MB |

| Qwen/Qwen3-32B (tensor_parallel_size=2) | 16 KB | 2 MB |

Note that the new vLLM KV cache layout yields a physical block size of about 0.5-2 MB, while in the old layout it is only a few KB. Combining this with the numbers we got from the GPU-CPU microbenchmark, we expect the DMA approach to have comparable performance, or slightly inferior (depending on the model), to the custom kernel approach.

End-to-end Evaluation of Copy Methods

In the next section, we use the two vLLM micro-benchmarks to compare the two variants of the offloading connector:

- The upstreamed version with DMA-based transfer function

- A patched version using the custom kernel from our GPU-CPU micro benchmark.

We purposely chose to present results with the worst case scenario for the offloading connector, using a model with a relatively small (0.5 MB) physical block size.

Figure 5: Single request TTFT (Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct, NVIDIA H100).

For the single request benchmark, we see the custom kernel yielding slightly better TTFTs, less than a 1ms difference for a 1K prompt, and up to a 15ms difference for a large 90K prompt. These results were expected given the results of the GPU-CPU micro-benchmark for a 0.5 MB block size. Models with a larger block size yield approximately the same result for the two variants.

Figure 6: Concurrent requests throughput (Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct, NVIDIA H100, 10000 prefill requests of 512 tokens).

However, for the concurrent requests test, we see DMA achieves better throughput than the custom kernel. The gain starts at around 5.5% at the 0 hit rate, and increases to around 15% at the 80% hit rate measurement.

These results are explained by the fact that the custom kernel approach interferes with the model computation, as both utilize GPU cores. For 0% hit rate, the custom kernel approach actually yields 6% worse throughput than without using CPU offloading at all. For 100% percent hit rate, there is no model computation in parallel to the CPU loading, and so the gap between the approaches shrinks.

We emphasize that we presented results with the worst case model for the DMA approach. The most common models have a bigger physical block size and hence favor the DMA even more. With Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct as an example, the DMA gained up to 32% more throughput over the custom kernel while matching its TTFT.

In summary, we see that our change in GPU memory layout allows us to utilize the DMA for KV transfers, achieving better overall throughput.

Evaluation Setup and Benchmark Code

To evaluate vLLM’s CPU offloading, we used the following setup:

- Single Ubuntu 24.04.1 LTS container

- Kernel 5.14.0-427.81.1.el9_4.x86_64

- Intel Xeon SapphireRapids 2.1Ghz (8 cores limit)

- NVIDIA H100 80GB HBM3

- 500GB DRAM

- CUDA Version: 12.9

- vLLM commit hash 2a1776b7ac4fae7c50c694edeafc1b14270e4350

- Flash Attention backend

- GPU prefix caching disabled (in order to evaluate CPU hits)

- GPU block size 16 tokens

- CPU block size 16 tokens

- De/Tokenization disabled

Our benchmark code can be found here.

What’s Next?

We’re continuing to enhance vLLM’s native KV offloading feature. Our next milestone is enabling the CPU KV cache to act as an intermediate tier for storage offloading.

As always, our top priorities remain correctness and performance. We invite you to try it out, share your results, and let us know if you encounter any issues.

Join the discussion: Share your use cases and feedback in the #feat-v1-cpu-offloading channel on vLLM Slack.